#UHateDisabledPeople

By Derek Newman-Stille

Twitter may seem like a strange place to create community with its short word counts and inclination toward simple answers rather than complex explorations, but it has become a space for disabled people to share our experiences with one another and to share experiences that we may have felt were ours alone. Disabled stories by disabled people are rare. Frequently publishers would prefer stories ABOUT disability written by abled people rather than narratives about disability by those of us in the disabled community. Yet we know there is a need for us to share our stories and to use our stories to advocate for change.

Frequently when people say that we need our stories to advocate for change, the assumption is that we are writing for an abled audience rather than a disabled one, however, one of our biggest tools for advocacy is our community. We have been able to achieve change through uniting as a disabled community and collectively engaging in activism.

Often we are expected to fight for disability justice quietly and accept what the abled majority tells us we are due, however, that hasn’t been effective in the past. We have never had rights “given” to us by a “compassionate” abled majority, we have always had to fight for our rights with committees, with demonstrations like climbing up the stairs of congress, and through legal action by disabled people. Being quiet has never served us, so we need to speak up and we need to make change loudly as a community. Disability justice comes from disabled anger.

Imani Barbarin has been a key figure involved in Disabled Twitter and has been devoted to disability justice through multiple fora including the Twitter hashtag #UHateDisabledPeople. Barbarin is a conversation starter, coining various twitter hashtags in order to begin conversations between disabled people and evoke change. As a disabled black woman, her work is intersectional, drawing on disability studies, but also a critical race perspective, and a feminist outlook. Barbarin has been a key figure in exploring disability representation, disability culture, and inclusion.

Barbarin’s hashtag #UHateDisabledPeople is in-your-face, powerful, and expresses the NEED for change. She expresses the idea that acts of ableism ARE acts of hatred toward disabled people. This hashtag has allowed people to come together in expressing our common experiences of ableism with a lot of responses by the community stating “I’ve experienced the same thing”

Some key tweets that have come up are:

Dr. Laura Dorwart points out in her Tweet “If you hear that a violent crime has been committed against a disabled person and your first thought is that the loved one who did it must have a good reason or deserve sympathy, #UHateDisabled People.

Dr. Dorwart points out that people often dismiss acts of murder against disabled people as “for the best” or “an act of love”, thus excusing the family members who murdered them. Frequently this is used as an excuse to get people out of murder charges when the victim has been a disabled person.

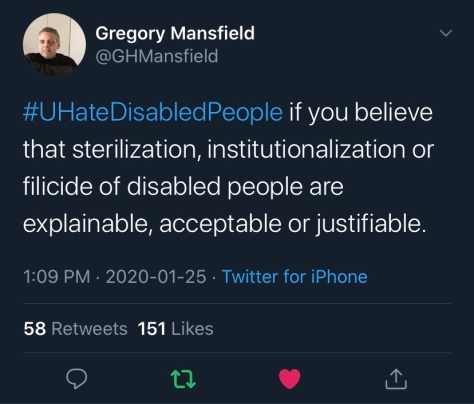

Gregory Mansfield points out further serious crimes against the disabled population in his tween “#UHateDisabledPeople if you believe that sterilization, insitutionalization or filicide of disabled people are explainable, acceptable or justifiable.”

Yet these tweets don’t only express radical acts of violence against disabled people, they also illustrate everyday ableisms and the way that the language of ableism is entrenched in every aspect of our society.

Charles Hughes points out that ableist society can only view us as “good cripples” when we are being “inspirational”; “If you love us when we’re adorable or ‘inspirational,’ but try to shut us down when we’re assertive or uncompromising, then #UHateDisabledPeople”. Hughes brings attention to the common trope of the “good cripple”, and the notion in ableist society that disabled people constantly need to be grateful for even the basics of accommodation or support afforded in our society.

Eli points out in their tweet issues around the unemployment of disabled people and the fact that it results from ableism and the entrenched belief that disabled people can’t work while ablist people still say that we disabled people should “get a job”. Eli states “When you think disabled people should get a job but you won’t hire us #UHateDisabledPeople” Eli illustrates the contradictory messages from our ableist society that we SHOULD work, but simultaneously that we CAN’T work.

Imani Barbarin observes the entrenched idea that disabled people don’t need to leave their houses and therefore don’t need to be accommodated by public spaces or public services when she states in her tweet “If you can’t think of a reason for disabled people to leave their house, other than to go to the hospital, UHateDisabledPeople”. This is a key issue since Barbarin and others on Twitter have been recently talking about rideshare and other services denying access to disabled people and then leaving us bad reviews because those services refused to accommodate our needs as disabled people (for example, denying access to people with service dogs, refusing the delivery of food to people with mobility disabilities).

Several people have brought attention to the assumption by the public that disabled people are “faking it”. For example, “Lilo the Autistic Queer” states in their tweet “if you harass strangers because you don’t think they should park in the accessible spot and/or sit in the accessible section on the bus/train #UHate Disabled People.” “Lilo the Autistic Queer” observes that people often act as though if they can’t immediately see our disabilities then we must be “faking it”.

Catherine Paul elaborates on this entrenched belief that disabled people are faking it, stating “If when you see a chronically ill person having a good time, you think they must be faking their illness, #UHateDisabledPeople.” The social assumption that we disabled people are “faking it” means that a huge amount of money is wasted on investigations into our claims of disability and often results in huge amounts of money that should be allocated to disability supports instead being allocated to investigations into our disabilities. So strong is this entrenched belief that disabled people are “faking it”, that people on the streets frequently believe they have a role in telling us they don’t believe we have disabilities or attempting to kick our canes out from under us or push our mobility devices. Indeed, Kaitlyn @BlytheByName points out the experience of purposely being bumped into in this tweet: “When you purposefully bump into me while I’m walking with my cane to test if I ‘really need it’ UHateDisabledPeople”.

Walela Nehanda illustrates how often disabled people are assumed to be “faking” their disability or trying to “scam” or “cheat” the system by saying “If you beleive disabled people are ‘faking’ our conditions because our disabilities don’t present in a way you’re accustomed to or because you think we are trying to ‘scam’ people or ‘cheat’ the system #UHateDisabledPeople”. Frequently abled people assume that they should be able to immediately look at us and then diagnose us with a glance and dismiss us as non-disabled when they can’t see our disabilities at a glance.

Not surprisingly, abled responses have varied from dismissing disabled people’s experiences to threats and doxxing.

“Diary of a Disabled Person” states “Okay, now I’m getting actual abuse from people over #UHateDisabledPeople, mocking my assumed lack of intelligence and inability to speak. Is it going to stop me? No fucking way. Is it going to get you reported? Damn right it will. Each and every one of you should be ashamed”. “Diary of a Disabled Person” is not the only person to receive threats, comments about their intelligence, and comments about their right to speak. This is happening across the hashtag.

“Dame DuhLaurien” dismisses the experiences of disabled people by saying “I think ‘hate’ is an awful strong word for the kinds fo things I’m seeing complained about in the #UHateDisabledPeople tweets but regardless cant we get #ULoveDisabledPeople.” In this, “Dame DuhLaurien dismisses the experiences of disabled people as minor, even though many of these tweets involve discussions of physical violence, exclusions of rights, and outright murder (as illustrated above). “Dame DuhLaurien” calls these experiences “complaining”, reinforcing the idea that disabled people shouldn’t express our frustration with everyday ableisms. “Was God In The O.R.” responds to “Dame DuhLaurien” by saying “Because y’all don’t love disabled people Lauren. Disabled people are denied access to food delivery, rideshare services, and public transportation, DAILY. And when we get on the internet to vent amongst ourselves, we’re made fun of, threatened, and doxxed. #UHateDisabledPeople”. “Was God in The O.R.” points out that people often use the words “we love disabled people” while continuing to perpetuate our oppression on a daily basis, illustrating that we, as disabled people feel the constant hate from an ableist society.

“TheDisabledEnthusiast” responds to “Dame DuhLaurien”‘s post with “If you think disabled people have to call out ableism in a way that’s more comfortable to you, #UHateDisabledPeople. You didn’t even bother to understand or sit with the meaning of the hashtag before you decided you were too uncomfortable and needed to shut it down.” “TheDisabledEnthusiast” points out the snap response that abled people have when being called out for their ableism and the instant response of tone policing disabled people rather than listening and thinking about what we are trying to express.

Imani Barbarin “Crutches&Spice” responds to all of the violence against the #UHateDisabledPeople hashtag by saying “people can troll my hashtags all they want. 1. They’re contributing to the numbers. 2. They’re proving my point. 3. The people who didn’t believe us can no longer ignore how widespread the problem is. Thank you for your time”. Barbarin powerfully points out that all the people who are denying the violence against disabled people only need to look at the violent responses to our tweets in order to see the entrenched ableism against us. Yet, she also points out the power of disabled twitter by observing that when our voices come together and we express the violence we’ve experienced – even if it is only by re-tweeting or liking a post – we are illustrating the common violence that we all experience.

Hashtags like those created by Imani Barbarin illustrate the power of our collective voice as disabled people. They are a way of creating community and collectively pouring out all of the violence and hatred we have experienced. Sharing a Twitter thread like this is confirmational for us, illustrating that we are not alone in our experiences. #UHateDisabled people is a strong hashtag because strong language NEEDS to be used. We are experiencing systemic violence and are constantly told to be quiet and accept the violence we are experiencing every day. Hashtags like this illustrate the power of collective storytelling, the power of sharing our narratives together and giving voice to everything that has happened to us. They create community as they advocate for change. As Barbarin states “The people who didn’t believe us can no longer ignore how widespread the problem is”.