By Derek Newman-Stille

I frequently get asked why I look at portrayals of disability in fiction. I am often told that I should look at something “real” and “substantial” like policy.

I find this an interesting assumption. People frequently assumed that marginalized identities are going to be best changed through policy and politics, but policies are shaped by social consciousness, by the realm of ideas. Fiction is about the realm of the possible, the realm of ideas, and it is ideas that make changes more than policy. Policies won’t change social attitudes unless there is a social receptiveness to these changes.

I frequently think about this in terms of requirements for accommodation in building codes, and the notion that undergirds this: “minimal compliance”. Minimal compliance with building accessibility codes mean that people can continue to view disability as a PROBLEM, as an issue that doesn’t need to be accommodated, but instead needs to be appeased. This means that buildings often have spaces that don’t really fit disabled bodies, but instead fit codes. Disabled bodies are still viewed as non-viable in these spaces, perceived as a barrier to an easy build rather than a necessary inclusion. Rather than viewing us as needed and essential participants in these spaces, we are viewed as inconvenient obstructions.

Fiction provides a space for radical rethinkings of our social spaces, challenges to a system that is content with our erasure. Fiction invites society to radically re-imagine our perceptual frameworks, our entrenched beliefs and the things that we consider self-evident.

Yet, our fiction is produced from the moulds that have been created previously, from our social frameworks and from our existing taken-for-granted understandings of the world. Our fiction, and our ways of imagining disability are fundamentally problematic, limited, and actively damaging. They reproduce ideologies that push disabled bodies further to the fringes and influence policies that don’t really include disabled bodies and often actively exclude us.

Our fiction, our imaginations, need an infusion of something new and potent, something that radically reconsiders not just literary tropes, but imaginative possibilities. We need a radical reconception of the way that disability occupies our imagination, challenge images that reduce us, and open up new possibilities for discourse.

Critical explorations of popular culture, literature, art, imagination, are not just things in the realm of academia. We should all be radically reconsidering our portrayals, critically questioning them, discussing them, and producing something new.

Tag Archives: stigma

Dis Arts

By Derek Newman-Stille

Frequently, when people see the words “disability” and “art” in the same sentence, they assume that this means “art therapy”. This is partially because of the way we frame “disability” as something that always means “working toward being fixed” or “working toward a cure”. This idea is fundamentally ableist and assumes that disabled people only live in the context of medicalized lenses and that disabled people are only interested in being “fixed” – i.e. made into able-bodied people.

Art Therapy can be a worthwhile venture for people who are interested in therapeutic qualities of art and expression, but it is important to recognize that Dis Arts (art work by people with disabilities) is not the same as art therapy. Dis Arts is an expressive art form that may or may not stem from bodily experience. It is an art that expresses a disabled world view. It does not always have to be art that is specifically and noticeably about disability, but, rather, can be the expressions of a disabled person about other aspects of their lives, wider political commentaries, or expressions of beauty (art for art’s sake).

I used to separate my disabled identity from my artistic identity, believing that I was creating fantasy art that had nothing to do with my disabled identity until people started to refer to me as a disabled artist. I had to pause and reconsider how my art reflects disability. I noticed that my art did show an interest in representing the body, and an interest in representing alterity (Otherness). As I was thinking about disability and art, I started to think about early diagnoses that I got from doctors about my learning disabilities. I was told early on that I would not be able to do art work because I have a fine motor disability. In fact, my early art work was described as consisting of “just scribbles” and early assessments told me that my “fine motor control is still quite immature”. These statements were repeated in later assessments even though I felt a compulsion to create art, to give context to the ideas in my imagination. In that way, art became a mechanism for me to resist hegemonic descriptions of my body. I refused to let my body be limited by the narratives that were imposed on it, so I devoted time to my art work.

As I reflected on the idea of my art work being a resistance to narratives imposed on it, I realized that the act of making art itself was linked to my disability. It became something that stemmed from a resistant Crip empowered perspective. Even when I wasn’t creating art that specifically referenced my disability, my art was still a Dis Art, a work of counter-narrative to the medicalization of my body.

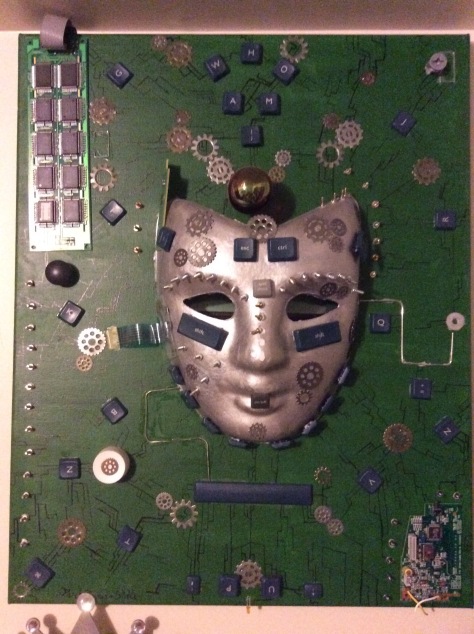

After encountering the work of other Dis Arts performers and creators, I decided to venture into my own Dis Art and created several pieces that stemmed from my body itself, using the canvas as an extension of ideas about my body. I quickly found that the best medium for these art pieces was mixed media since mixed media, like my own body, is a conglomeration of objects, texts, and styles of art. It fit with my ideas of my own body as a composite of multiple different views and texts. I combined objects that seemed to resonate with my body into new images, focussing on my spine (for my spinal disability), my brain (for my learning disabilities), and ideas of the viewer, because people often stare at the disabled body. I assembled a series of mixed media works of art into a show titled Identity Masquerade: The Queer Crip Art of Derek Newman-Stille that I displayed as part of the Queer Coll(i/u)sions Conference, allowing the work to speak to people without my providing context for these pieces. I wanted people to reflect on the way that they saw these works of art, and to think about the way that the act of staring at art could reflect the way that people stare at the non-normate body. I emphasised this focus on staring by including mirrors in images that forced the watcher to stare at themselves as they tried to stare at the work of art. I included images of spines mixed with images of nude bodies to represent ideas of our bodied being rendered nude before the Gaze.

Coming to Dis Arts was an act of self-discovery for me, an act of empowerment, and an act of vocalizing things that extended beyond words.

Dis Arts are complicated because our disabled identities are complicated and are never fixed as one thing. Disabled bodies are fluid, and they intersect with our other identities as well as connecting to a community of artists who identify as disabled. There is a different kind of viewing in Dis Arts works, and it is one that involves the body, that implicates the body, and that invites the body into the art work being produced. Dis Arts can be an intensely political art – one that speaks to inaccessibility, a history of being Othered, the power of community, and the possibility of change.